Abstract

Background:

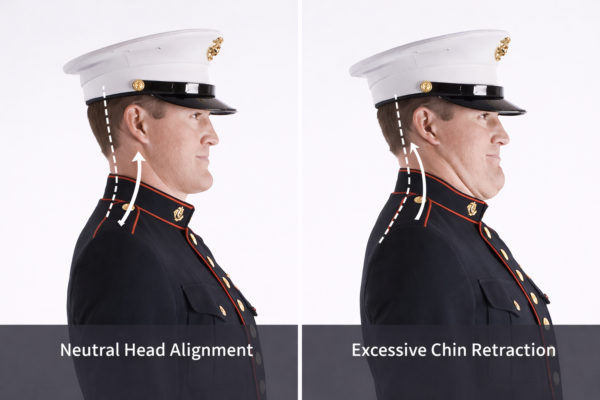

Military and cadet training environments emphasize rigid posture and uniform precision. Certain well-intended practices—specifically excessive ceremonial belt compression and sustained chin retraction—may unintentionally compromise respiratory and musculoskeletal function.

Objective:

To examine the combined physiological and operational effects of cervical spine straightening and diaphragmatic restriction in posture-intensive training environments and to propose doctrine-compatible mitigation strategies.

Methods:

This narrative analysis integrates musculoskeletal biomechanics, respiratory physiology, occupational health literature, and operational observations from military and cadet training contexts.

Results:

Excessive chin retraction reduces cervical lordosis, increasing spinal loading and muscular demand, while excessive belt compression restricts diaphragmatic breathing and promotes chest-dominant respiration. Together, these factors reduce endurance, degrade vocal projection, and increase long-term injury risk. An existing institutional uniform design demonstrates effective mitigation without compromise to ceremonial standards.

Conclusions:

Postural and respiratory strain resulting from overcorrection represents a modifiable readiness risk. Refining posture instruction and uniform fit standards preserves discipline while protecting performance and long-term health.

Keywords:

Military posture; cervical lordosis; diaphragmatic breathing; training injury prevention; ceremonial duty

Introduction

Military posture training is designed to instill discipline, uniformity, and endurance. However, posture cues and uniform practices that exceed physiological necessity may inadvertently compromise function. This paper examines two such practices—excessive chin retraction and abdominal compression—and their combined impact on readiness.

Posture, Cervical Alignment, and Respiratory Mechanics

The cervical spine’s natural lordosis supports load distribution, airway mechanics, and neurologic function. Sustained chin retraction drives cervical flexion, flattening this curve. Simultaneously, tight waist compression limits diaphragmatic excursion, forcing reliance on accessory breathing muscles.

Together, these practices alter posture–respiration coupling critical to endurance and voice production.

Download the following papers:

- White Paper – Respiratory Consequences of Chest-Dominant Breathing Induced by Tight Ceremonial Belt Wear in Ceremonial Guardsmen

- White Paper – Military Neck: Cervical Spine Straightening Associated With Excessive Chin Retraction in Military and Cadet Training

- DoD Memorandum – Preventable Postural and Respiratory Risk Factors in Military and Cadet Training Environments

- Policy Brief and SOP Annex – Preventable Postural and Respiratory Risk Factors in Honor Guard Operations

Operational and Clinical Implications

Affected personnel may experience:

- Reduced ceremony and training endurance

- Neck pain and headaches

- Impaired vocal projection

- Increased musculoskeletal strain

- Long-term postural dysfunction

Cadet populations are particularly vulnerable due to repetition and developmental plasticity.

Institutional Mitigation Example

The blouse-supported ceremonial belt system used by Marines at Marine Barracks Washington demonstrates that functional breathing and cervical alignment can be preserved without relaxing appearance standards.

Discussion

Discipline should reflect controlled alignment, not forced rigidity. Evidence-informed refinements to posture instruction and uniform fit enhance sustainability without diminishing military bearing.

Recommendations

- Replace exaggerated chin retraction with neutral alignment cues

- Permit diaphragmatic breathing during belt fitting

- Educate instructors on cervical and respiratory biomechanics

- Integrate posture considerations into training risk management

Conclusion

Preventable postural and respiratory strain represents a readiness issue, not a cosmetic one. Aligning training practices with human biomechanics strengthens endurance, professionalism, and long-term force health.

References

Bordoni, B., & Zanier, E. (2013). Anatomic connections of the diaphragm. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare.

Hodges, P. W., & Gandevia, S. C. (2000). Activation of the human diaphragm during postural tasks. Journal of Physiology.

Kolar, P. et al. (2012). Postural function of the diaphragm in persons with and without chronic low back pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy.

McConnell, A. (2013). Respiratory Muscle Training: Theory and Practice. Churchill Livingstone.

Mead, J. (1960). Control of respiratory frequency. Journal of Applied Physiology.

Ritz, T., & Roth, W. T. (2003). Behavioral interventions in asthma and dysfunctional breathing. Journal of Psychosomatic Research.

Sapienza, C., & Hoffman-Ruddy, B. (2013). Voice Disorders. Plural Publishing.

Smith, J. et al. (2017). Effects of abdominal binding on pulmonary function. Respiratory Care.

Borden AG, Rechtman AM, Gershon-Cohen J. The significance of lordosis of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960.

Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, et al. Modeling of the sagittal cervical spine as a method to discriminate hypolordosis. Spine. 2002.

McAviney J, Schulz D, Bock R, et al. Determining the relationship between cervical lordosis and neck complaints. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005.

Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2017.

Quek J, Pua YH, Clark RA, Bryant AL. Effects of thoracic kyphosis and forward head posture on cervical range of motion. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013.

Yoo WG. Effect of chin tuck exercise using a pressure biofeedback unit on neck muscle activation. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015.