The photo at the top of the page shows what is called a “Committal Shelter” or a “Committal Pavilion”. For a more modern, utilitarian structure, “Committal Terrace” is also sometimes used to describe a paved, roofed area specifically set aside for the service to take place away from the mud or grass of the grave site.

- A Porte-Cochère: In older or more formal cemeteries, this is a large, roofed structure that vehicles (like a hearse) can drive under. It’s often used as a covered gathering point for the service so people can step out of their cars directly into a dry, shaded area for the ceremony.

- A Lychgate (or Lichgate): Historically, this is a roofed gateway at the entrance to a churchyard or cemetery. While traditionally used to rest the casket before entering the grounds, larger modern versions are sometimes built to act as a permanent covered spot for outdoor services.

Why these are used instead of a Chapel

Unlike a chapel, which is a fully enclosed building, a shelter or pavilion is preferred in many modern cemeteries for a few reasons:

- Airflow and Nature: It allows the service to feel like it is “outdoors” while still providing a solid roof to block rain or direct sun.

- Accessibility: They are almost always built on flat, paved ground near a road, making them much easier for funeral processions and elderly guests to access than a grassy hillside.

- Efficiency: Especially in veterans cemeteries, burials happen in a specific sequence. Using a central shelter allows the family to have their 20-minute service while the cemetery crew prepares the actual burial site nearby.

Terms to Know

- Directional Flow: The path from the hearse (what we call a “coach”) to the catafalque.

- Stationary Catafalque: Many modern shelters have a permanent stone or concrete plinth.

These structures work well when their orientation supports ceremonial movement — and fail when they do not.

Why These Decisions Are Made

Often, the “wrong” setup occurs because the architect prioritized site aesthetics (like a mountain view) or parking accessibility over ritual mechanics. The permanent orientation is usually decided to maximize the number of people who can fit under the roof, sometimes at the expense of how the casket actually arrives at the center point.

The “Rules of the Foot”

The “Rules of the Foot” are a blend of theological symbolism, superstition, and practical physics.

1. The Rule of Directional Movement (Symbolic)

The primary rule is that the deceased must always travel feet-first.

- The Symbolism: This mimics the natural way a person walks. It represents “walking” into the next life or towards the altar.

- The Superstition: In many European traditions (particularly Scottish and Irish), carrying a body out of a home or into a cemetery head-first was forbidden. It was believed that if the head went first, the “spirit” could look back at the living and beckon them to follow or find its way back home to haunt the house.

- The Hospital Connection: Even today, many hospitals and hospices have an unwritten “Rule of the Foot” where patients leaving the OR or a room are moved feet-first. Moving a patient head-first is often seen by staff as a “bad omen” or a sign that the patient has already passed.

- Airway and Clinical Monitoring: Pushing a patient feet-first allows the medic at the “head” of the stretcher to maintain a constant, unobstructed view of the patient’s face, chest, and airway. This ensures immediate recognition of, and access to, a patient who stops breathing or requires emergency intervention during transit.

- Protection from Impact: In any transport, the leading end of the stretcher is the most vulnerable to accidental contact with objects. Moving feet-first ensures that the patient’s lower extremities act as a buffer, shielding the head and cervical spine from potential jarring or traumatic impact.

- Vestibular Stability and Orientation: Moving head-first can cause significant disorientation and motion sickness. Feet-first transport allows a conscious patient to use their peripheral vision to anticipate turns and “see” where they are going, preventing the “falling” sensation triggered by the inner ear when moving backward at speed.

2. The Rule of Weight Distribution (Practical)

While the symbolism is beautiful, the physics of a casket carry usually dictates the “foot” rule.

- The Center of Gravity: The human body is top-heavy; the torso and head account for the vast majority of the weight.

- The “Heavy End”: By moving feet-first, the lead pallbearers (at the foot) handle the lighter end, allowing them to navigate the path and set the pace. The “anchors” at the head end carry the bulk of the weight but have a clearer view of the lead’s movement.

3. The “Liturgical Exception” (The Rule of the Flock)

There is one major liturgical exception to the Rule of the Foot: The Clergy.

- Laypeople: Are carried into a church feet-first so they face the altar (the “East”). When they rise at the Resurrection, they will be facing the Risen Christ.

- Priests/Ministers: Are often carried into the church head-first. This is so that even in death, they are positioned to lead and face their congregation (their “flock”). At the Resurrection, the priest stands up and is immediately facing the people he served.

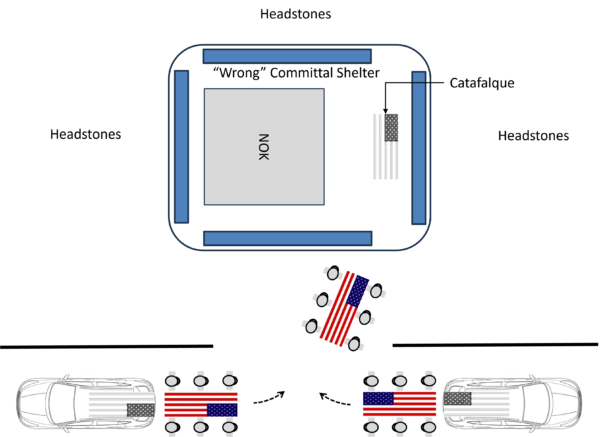

The “Forced Error” in Shelter Design

A conflict arises when a Committal Shelter is built with a “one-way” or “dead-end” orientation.

The Conflict: If the coach pulls up to a shelter where the only entrance puts the pallbearers at the back (foot-end when the casket is placed) of the catafalque, they are faced with a professional’s dilemma.

- Option A (The Head-First Entry): They enter head-first to ensure the head is at the left the family. This violates the “Rule of the Foot” and can feel “wrong” to seasoned bearers.

- Option B (The Blind Pivot): If the team is untrained, they may attempt a full 180-degree rotation at the shelter to preserve feet-first entry. This creates visual disruption, breaks ceremonial flow, and should never be done.

The “Up and Face”

For Air Force Ceremonial Guardsmen, we are trained to perform two exits from the coach. The following explanations are minimal for you to get the idea of what we do. The pallbearer team knows beforehand what sequence is required.

- Exit Sequence 1: “STEP!” This command signals the team to sidestep away from the coach. We step away a certain number of steps and then rotate a number of steps (numbers change over the years, 6 & 3, 5 & 5, etc.). That rotation brings the foot of the casket 90 degrees to point the direction of travel. From here the command is “UP!” we bring our heads to face straight forward, and then “FACE!” where we face the foot end of the casket. We march off to the where the casket will be placed.

- Used for long carries and is the most used sequence for all the services.

- Exit Sequence 2: “UP!” we bring our heads to face straight forward, and then “FACE!” where we face the foot end of the casket. We march off to the where the casket will be placed.

- While command language varies by service, the underlying mechanics are consistent across military and ceremonial pallbearer training and this sequence is used for short carries and when there is an impediment (monument, tree, etc.) in the path from the coach to the resting place (grave, catafalque).

Minimizing the Awkward Look

Notice in Exit Sequence 1 that the casket is not turned more than 90 degrees. Also notice that in Exit Sequence 2 the casket is not rotated at all. There are several techniques used to turn a casket or turn pallbearers, but the concentration is always to minimize visual “friction” and provide the family the best experience as the team honors their loved one.

Design Rule:

A committal shelter must allow a pallbearer team to exit the coach, orient feet-first, and approach the catafalque without exceeding a 90-degree rotation or breaking formation.

The Takeaway for Architects and Cemetery Managers

The lesson for those who design these structures is simple: Consult the bearers. A permanent structure should never force a team to choose between ritual integrity and ceremonial grace. A shelter must have enough “staging apron” to allow for a clean rotation and enough clearance for the team to maintain their “box” without breaking files.

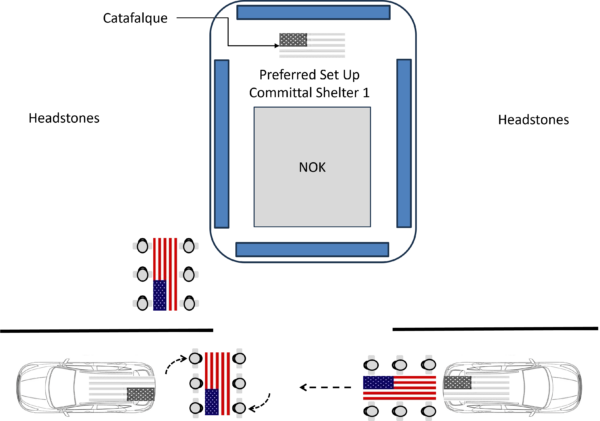

A Preferred Set Up

This is going to be the set up that is preferred rather than the one above.

What “Preferred 1” Does Well

1. It Maximizes Flexibility

Preferred 1 shows:

- A larger approach apron

- More implied tolerance for vehicle positioning

- Greater adaptability for varying site constraints

This version is excellent for:

- Retrofits

- Older cemeteries

- Sites with multiple entry points

- Locations where terrain or legacy layout limits ideal alignment

In other words, Preferred 1 is pragmatic.

2. It Anticipates Real-World Variability

This diagram acknowledges:

- Coaches don’t always stop perfectly

- Processions don’t always arrive identically

- Funeral directors may stage differently day to day

That makes it attractive to operational managers.

Where “Preferred 1” Falls Slightly Short

1. It Allows Interpretation

And in ceremony, interpretation invites error.

Preferred 1 still visually permits:

- Minor on-the-fly adjustment

- Decision-making at the shelter

- Subconscious “we’ll fix it here” thinking

You and I both know experienced teams can handle that —

but design doctrine exists to protect the least-experienced team on its worst day.

2. The Flow Is Not as Inevitable

Compared to Preferred 2:

- The directional authority is softer

- The shelter doesn’t command movement as clearly

- There’s slightly more visual ambiguity

Nothing is wrong — but nothing is forced either.

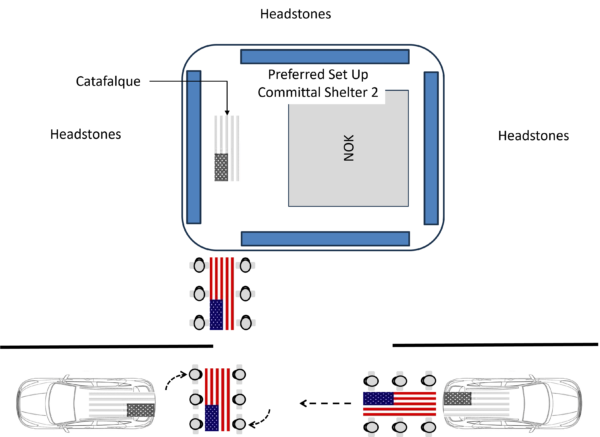

The Best Practice Set Up

Why Preferred 2 Wins as a Published Standard

Preferred 2:

- Removes choice

- Eliminates correction

- Prevents hesitation

- Reduces cognitive load

It communicates:

“If you build it this way, the ceremony cannot go wrong.”

That is the essence of best practice doctrine.

Dedication

This article is dedicated to the Team Holloman AFB Steel Talons Honor Guard. The team contacted me to get feedback on their approach technique using the head-first carry and I ended up writing this to ensure everyone out there knows of this technique. Even when those around you insist that you are doing something wrong, relying on your training—even when you do not yet fully understand the reasoning behind it—is often the best course of action.

The team MSgt Casey Chillemi, (S)Sgt Cody Owens (congratulation on the upcoming promotion!), SrA Malakye Vergara, SrA Madeline Johnson, A1C James Taylor, and A1C Landen Keo-broad.

Thank you, team. You did an excellent job today!